Including soil texture in a proactive approach to micronutrient deficiencies

Lara de Moissac

Precision Agronomist

lara.demoissac@swatmaps.com

On the Prairies, micronutrients such as copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn) are variable in their distribution of total and available amounts across landscapes and fields, and because of this, site- and crop-specific management is required.

Soil extractions for testing plant-available micronutrients are a good start to determining deficiency levels and for pinpointing areas of fields that may need a micronutrient top-up. However, a soil extraction sometimes does not extract all the nutrient because the nutrient is bound in unavailable chemical fractions in the soil or has transformed into a different chemical species. Due to this, the ppm of micronutrients can be thought of more like guidelines and a reactive approach is often taken to mitigating deficiencies with in-season foliar micronutrient applications.

Leached, acidic, or sandy soils are low in most micronutrients for the same reason they’re low in macronutrients; the parent materials were generally low in nutrient elements to begin with. In the case of organic soils, micronutrient content depends on the extent of leaching.

In mineral soils, micronutrient deficiency usually occurs in coarse-textured soils containing low organic matter (e.g. Grey Luvisolic and Grey Black transitional soils). Organic or peaty soils are also susceptible to deficiency and are often highly responsive to Cu fertilization due to low mineral content, as is the case in central and northern Alberta and Saskatchewan and central Manitoba. In high pH and high calcium carbonate-containing soils, surface adsorption of Cu and Zn are promoted, therefore reducing their availability to plants.

So, what if a more proactive approach to micronutrient deficiencies could be taken by using soil texture to predict shortages, in addition to soil testing, tissue testing, crop yield, and nutrient removal?

Recent research out of the University of Saskatchewan by Rahman et al. (2021) examined how soil texture as well as other soil properties, could help predict micronutrient deficiencies. More specifically, their study found that high sand content and low organic matter were identified as important soil properties that contributed to Cu, Zn, and B deficiency.

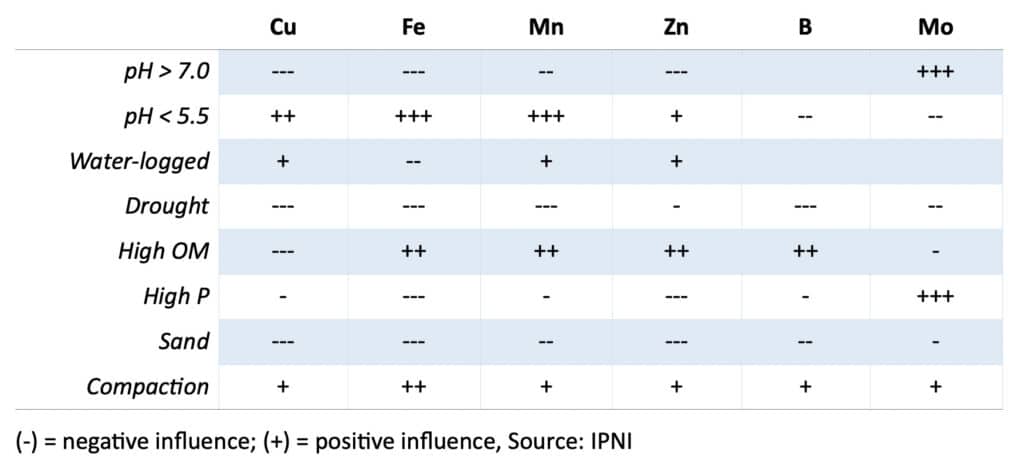

This theory has merit from the perspective of soil texture, because of sand’s inability to hold on to nutrients due to a lack of cation exchange sites and generally lower organic matter, that a higher clay content soil would have. (See the negative influence of sand on availability of micronutrients in the table below from IPNI)

Table 1. Influence of environment and soil conditions on micronutrients

Furthermore, among the soil attributes measured in Rahman et al.’s study, soil carbon and sand content appeared to be the most important in controlling the distribution of micronutrients among different soil pools, based on specific solubility ranges.

Researchers in Alberta established that the distribution of Cu through the soil profile is more important than surface soil values for determining the probability of a deficiency in a crop (Penny et al., 1992), which highlights the importance of thinking in 3D when it comes to soils.

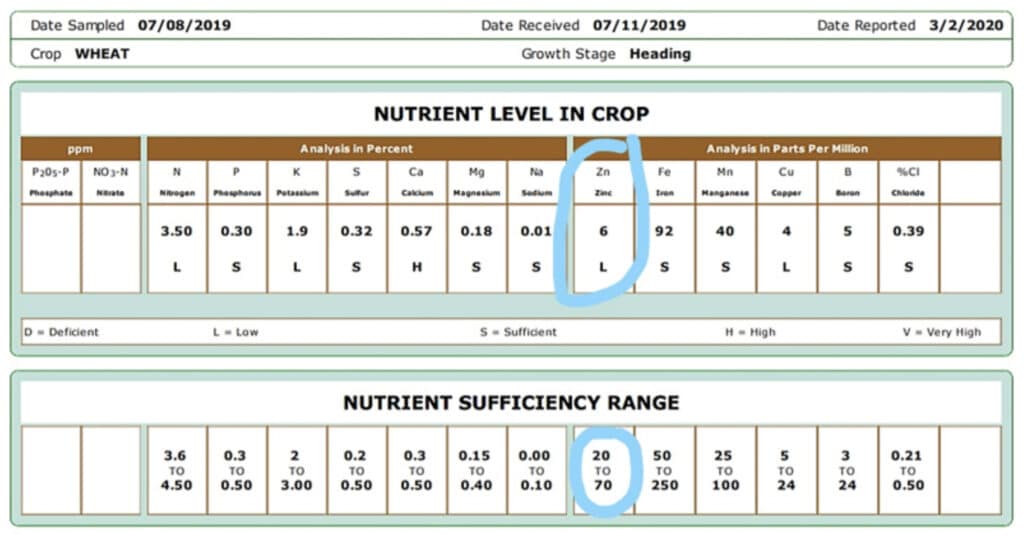

The mechanisms behind Zn deficiency symptoms showed up in fields in the Wadena and Archerwill, SK areas — areas with high sand and low organic matter content. The soil pH of both these fields in the 0 to 8” depths was around 8 and 8.1, respectively, and Figure 3 shows how sandy the field at Archerwill was (in addition to soil testing from the previous fall).

When it comes to micronutrient diagnosis, the most conclusive approach still involves soil and tissue testing, as well as implementing some test strips. The patchy nature of micronutrient deficiencies make them a good candidate for variable rate prescriptions through the SWAT MAPS ECOSYSTEM, as the deficient areas can be targeted with a high-resolution prescription.