Knoll Management with SWAT MAPS

I was driving along this spring when I noticed a field with a small area taken out of production. This was obvious, as the field was in potatoes last year (2020) and these areas were covered in sod. The area taken out of production was clearly an eroded knoll.

This had me thinking… to farm an area like this or choose to take it out of production altogether is kind of an “all or nothing” approach. It is either farmed the same as the rest of the field, or not farmed at all, but we know that that knoll did not just go from being productive to unproductive overnight. For every knoll that has been taken out of production altogether, there must be many acres that are somewhere in between… not fully productive, but not to the point where we would consider taking them out of production.

Upon review of some satellite imagery and LiDAR elevation data for this field, I found out that there were three places taken out of production on this field, all due to their landscape position. It is not uncommon to see a knoll taken out of production in certain areas of P.E.I. where topography is variable. These knolls are not always extreme slopes, or areas of a field with huge elevation changes.

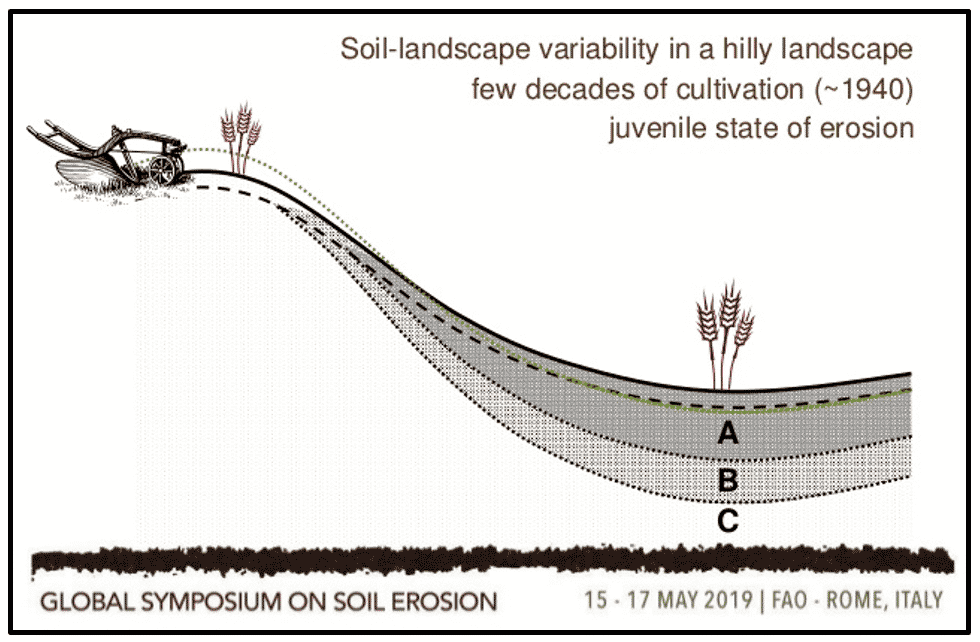

Dr. David Lobb of the University of Manitoba estimates that soil erosion costs Canadian Farmers over $3 Billion per year due to lost productivity (Arnason, 2019). There is no doubt that we have had a lot of topsoil movement due to wind, water and tillage erosion in Prince Edward Island – something that is unavoidable in potato production. Growers are doing an excellent job in adapting/improving management practices to keep valuable topsoil in place by planting cover crops, installing soil conservation structures to break up long slopes, using conservation tillage and more. While these practices will slow down the impacts of erosion, they are not a quick fix for issues that have taken decades to occur. A study from Prince Edward Island by DeHaan et al. (1999) found “Visual observations during harvest indicated substantial reductions in yield on the highly eroded sections of the field. Along with the reduced yields, highly eroded areas appeared to have smaller tubers and a higher population of stones.”

With SWAT MAPS we can map and measure these areas. But even more important than measuring them, we can manage them! This is not possible with a grid sampling strategy, which is mainly describing soil chemistry variability. A grid sampling strategy does not know an eroded knoll from a well-drained highly productive lower slope position. SWAT MAPS uses accurate topography models that come from high resolution LiDAR or RTK elevation data in combination with electrical conductivity data to map where water sheds, where it collects, and where erosion has likely occurred. Knowing this, we can then precisely choose where to pull soil samples from so that eroded knolls are grouped together – and not lumped in with more productive areas of the field.

A satellite image showing weaker performing areas in a field from July, 2019. SWAT MAPS clearly indicate these are Zone 1 hilltops. The driest parts of a field, which have likely experienced significant erosion over the years.

After these areas are properly mapped, we can then address them differently when we fertilize. With lost topsoil and lost yield potential, should these areas be fertilized and seeded the same as the rest of the field? Perhaps yield goals could be adjusted, or seed rates tweaked depending on the crop. For a high value crop such as potatoes, we may look to space seed further apart and manage risk, reducing stress per plant in the driest parts of the field. For wheat, the strategy could be totally different, and due to a higher seed mortality rate on these knolls we could increase seeding density to achieve a more uniform stand. “Soil building” crops such as sorghum sudan grass and pearl millet are becoming more common in potato rotations, and we can look at using VR equipment to increase seeding rates of those crops on these knolls to improve soil health and organic matter. There are many possibilities, but to properly manage them we need to measure them first.

Evan MacDonald

Precision Agronomist

evan@swatmaps.com